PC

T&P

| |

PERSONAL CONSTRUCT

THEORY & PRACTICE

|

Vol.5 2008 |

| PDF version |

| Author |

| Reference |

| Journal Main |

| Contents Vol 5 |

| Impressum |

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| EXPLORING STUDENT

TEACHER BELIEF DEVELOPMENT: AN ALTERNATIVE CONSTRUCTIVIST TECHNIQUE, SNAKE INTERVIEWS, EXEMPLIFIED AND EVALUATED |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nese Cabaroglu*, Pamela M. Denicolo** | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

* Faculty of Education, Cukurova University, Balcali/Adana,

Turkey

** Graduate School for the Social Sciences, University of Reading, UK |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

INTRODUCTION

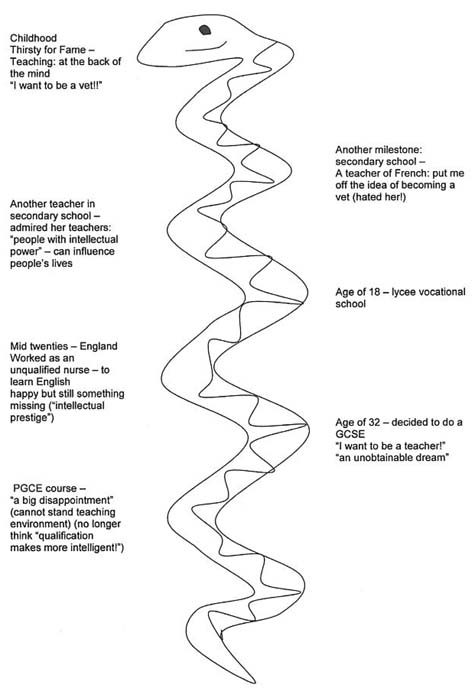

This report focuses on a particular technique, Snake interviews, used to resolve a conundrum that occurred during the course of a main study that sought to explore the beliefs about teaching/learning a foreign language of student teachers embarking on the study for a Postgraduate Certificate in Education (a teaching qualification), how those beliefs developed during the course and how the students themselves explained and interpreted their beliefs and any changes in them. Although the literature on teacher education suggested that the beliefs held by the student teachers are inflexible (Kagan, 1992) and that teacher education programmes are “not very powerful interventions” (Zeichner et al., 1987, p. 28), a preliminary analysis of the data when about 60% of the course had been completed demonstrated a continuum of belief stability from very stable to radically changed. At this stage the Snake interviews were introduced into the research study with a sample of the participants in order to gain further insight through the student teachers’ reflections on their beliefs, their consistency or development and their own proposed reasons for that stability or change. Although only a small sample undertook this exercise, the results illuminated the full data from the main study and suggested methodological advantages to encourage its future use. Thus this paper first provides sufficient detail about the design of the main study to give context. It then describes the process of the Snake interviews and the results from it, showing how they linked with and illuminated the analysis of the main data to give insight into belief resilience/development. Finally, there is a review of the benefits of this technique. THE STUDY PROCESS Design of the main study The research adopted a constructivist approach to investigate the development or resilience of student teachers’ beliefs. The student teacher was conceptualised as “a constructivist who continually builds, elaborates and tests his or her personal theory of the world” (Clark, 1986, p. 9). The main study was conducted using a convenience sampling strategy (Creswell, 1994), with 25 of 34 student teachers attending a 36-week teacher education course on MFL (Modern Foreign Languages) teaching at the secondary school level in England. The students received training in subject method, educational theory and professional studies and undertook sessions of school experience. The course model of learning to teach was explicitly reflective and experiential. Five students had abandoned the course part way through the study. A combination of various qualitative techniques (participant observation in the MFL Method Course, Student Teacher Fact Sheet, learning autobiographies, interviews, Snake technique and a questionnaire) was employed to collect multifaceted data for triangulation to facilitate validation. Each instrument served a different purpose: identification of the participants; seeking answers to each research question posed; triangulation purposes. The participant observation provided evidence of the students’ beliefs as they were enacted in the classroom at college. The Fact Sheet provided demographic data from each participant whilst the learning autobiography provided written accounts of student teachers’ language learning experiences and their related beliefs. Additionally, a series of three in-depth interviews elicited student teachers’ accounts of their beliefs and their perception of any developments in them. During each of the three personal interviews, conducted at different points in the course, the following aspects of language teaching and learning were addressed: the place of Modern Foreign Languages in the curriculum, the place of grammar teaching in language teaching, the characteristics of a good modern languages teacher and teaching, learner needs, the nature of learning and teaching. A protocol of open questions and optional probes were used to structure the interview on entry to the course, Time 1. For the interviews conducted at Time 2 (after observation in partnership school A and before the main block teaching practice in partnership school B) and Time 3 (after the main course activities were completed), the verbatim transcriptions of the previous interviews were used as a form of stimulated recall to facilitate reflection on any development in participants’ previously stated beliefs. A preliminary analysis of the data after the second interview but before Time 3 suggested that there were remarkable differences between what some student teachers said in their first and second interviews, while others were more consistent in their views, forming a continuum between apparently no change and radical change in beliefs about teaching and learning. In order to gain some insight into this diversity, snake interviews, which are described in the next sub-section, were conducted with three volunteers from the extremes of the continuum. It was expected that contrasting the data from ‘extreme’ cases might more readily reveal correlated factors. The Snake interview as a research instrument and its use in this study The Snake Interview (also known as ‘River of Experience’ technique) is a constructivist technique that is used to promote reflection on ‘critical incidents’ in the life history of participants (Denicolo & Pope, 1990). Fundamentally, the Snake is a diagrammatic flow chart that depicts some specified aspects of a person’s life related to the discussion focus (for an example of a Snake chart see the Fig.1).  Figure 1: Snake chart prdocued by ST14 The underlying principles in the use of this technique can be found in Kelly’s (1955) Personal Construct Theory. The Fundamental Postulate essentially notes that a person anticipates events through their personal constructions of reality while the Range Corollary - “a construct is convenient for the anticipation of a finite range of events only” – and the Experience Corollary – “a person’s construction system varies as he [sic] successively construes the replication of events” are relevant here. Pope and Denicolo, (1993, p. 540) elaborate: “Constructs evolve over time and are particularly influenced, consciously or unconsciously, by formative experiences”. They later suggest that, in order to understand the present, one needs to compare and contrast it with previous experiences and use the result to predict the future (Pope & Denicolo, 2001). They designed the Snake interview technique as a tool for understanding how critical incidents contribute to the formation of constructs elicited later in life. In contrast to pre-determined interview questions, the Snake interviews not only yield information concerning what a person believes but also provide clues as to what has led that individual to her/his beliefs by unravelling the consequential incidents in the personal history of the individual (Albanese, 1997). Above all, they enable “the participants to use their own words and to indicate issues which are personally important”, reducing interviewer bias (Pope & Denicolo, 1993, p. 541) and producing highly authentic and rich data. However, the uniqueness of the data individually produced can lead to data that is difficult to compare across cases while participants, in gaining a deeper understanding of their own constructs and their connections, may need to confront sensitive revelations about themselves. Thus, when using this technique the researcher should be attentive, perceptive and supportive (Iantaffi, 2004). The Snake interviews were used in this study to:

All three of the volunteers were female, two of them apparently changing their constructs about teaching, teacher and pupil roles between the two interviews while the third participant was a student teacher who seemed not to have changed at all in her construing of these concepts. The codes ST3, ST14, and ST16 are used to refer to these students to preserve anonymity. In each Snake interview, the researcher explained to the participant the nature of the snake chart and how one could be developed, using illustrative examples from different contexts, and then gave the instruction: Please visualise your development as a teacher. Draw it as a winding snake. Each turn in its body represents an important event, person, object or anything at all that influenced your attitudes and beliefs about language, learning and teaching modern foreign languages. Please annotate each turn of the snake with a few words to remind you of what stimulated/caused these developments. Both positive and negative influences are important and should be included. The participant was reminded that, because personally important issues were the concern of the study, she was expected to identify her own agenda for discussion but she was assured that she was under no pressure to discuss issues that made her feel uncomfortable. The participant was then left alone to reflect, visualise and then draw her Snake chart. Later, she was invited to explain and elaborate on each annotated turn on the chart. Each interviewee agreed that the interview could be audio-recorded and verbatim transcripts were produced later. Notes were also made during the Snake interview for follow up questions in Interview III to clarify or explore further some of the issues mentioned. Analysis The data from the Snake interviews and from Interview III were searched for patterns and then for common points in the three Snake charts across all three participants using content analysis techniques (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Moreover, the data obtained via Snake interviews from each participant were compared and contrasted with the data obtained from their three open-ended interviews and the other data sources to uncover themes and disjunctions. The overall aim was to identify from the data explanations in the interviewees’ own words for changing, abandoning, strengthening or maintaining constructs and beliefs about aspects of teaching /learning a foreign language. FINDINGS Three stories: findings from the qualitative analysis of Snake interviews and open-ended interviews I, II and III, fact sheets and autobiographies It is worth highlighting once again that only three student teachers from the main study group took part in the Snake interviews as exemplars of the extreme poles of the continuum of stability of views about teaching and learning found in participants in the same training course. The Snake interviews did indeed facilitate the interviewees to provide their reasons for the apparent differences, something that became very obvious especially when the transcripts were interrogated alongside other data sources. This allowed more relevant questions to be posed in the third and final interviews. For instance, during the second interview ST14 and ST16, when asked for the reasons for the dramatic changes in their views, referred only to their recent teaching practice experience while the Snake interview revealed how a range of experiences during the course seriously challenged previously acquired constructs about teaching and teacher roles. The next sections report findings from the analysis, for each of the three student teachers who took part in the Snake interview technique, of the data from the fact sheet, language learning autobiography, three sets of open-ended interviews, and Snake interviews and combines all these data to provide further explanations for these extreme cases. Resistance to change: ST3 Background ST3, a British student teacher in her 40s, did not seem to change or develop her beliefs throughout the year. She had: studied foreign languages and English for her degree; been teaching English for 14 years before starting the MFL teacher education course; declared a “love of the English language”; taught English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in the USA; continued working as a teacher of EFL when she later moved to Germany. Although initially she started teaching because she wanted to “keep her English up”, she enjoyed this experience because: teaching was a social event; had “good status” that earned her respect. When she moved to England, she decided “to do a mirror image: teaching German in England.” Needing a permanent day job, she decided to enrol in the teacher training course. Interview I She noted: the importance of learning other languages and about other countries; that learning a language involved a lot of concentration, patience, good memory and repetition; that grammar had to be taught “gently” so that it would not become dull. She conveyed a picture of a classroom with a lively atmosphere, full of humour and fun, in a relaxed atmosphere in which teachers were friendly and accessible. She favoured teaching through visual aids, perhaps using posters and pictures from pupils’ lives, and a variety of activities. Very often, she referred to her previous teaching experiences. On one occasion only, she referred to her own learning experiences in the past. Interview II At the second interview, although she expanded on the issues discussed in the first interviews, she indicated that none of the newly introduced issues were newly acquired; she had simply forgotten to mention them in the first interview. She claimed, when asked, that the observation in partnership schools had not influenced her beliefs; she had learned nothing but just “a few tricks” and some new activities. She added “I feel the same way that I did at the beginning of the course”. Interview III Again, she elaborated on previous ideas but did not change or add any new ones. Snake interview and comments The interviews with ST3 were shorter than the interviews with other participants in the study. Whenever a follow up question was used, she always provided brief responses, though not in any way unfriendly or reluctant. It was only the Snake interview data that revealed her concern with her status relative to teachers and pupils in schools, and to staff and other student teachers at the university: I’d been a fully paid, well-paid respected

teacher and asked my ideas. And then, all of a sudden you are a learner again,

‘you don’t know anything’ sort of thing. But it wasn’t that bad, I wasn’t

patronised very much. . . I think it was my own picture of myself as a student

teacher because the teachers were actually quite respectful of me because my

German was better than theirs…but I think it was my own image of myself

thinking: ‘Oh, you’ve got to go and observe. You’re nothing!’ ….That was the

sort of image I felt that I had… I thought ‘I’m just a student!’...It’s like

you’ve been driving for 20 years and then suddenly you’ve got an ‘L’ plate on

your car again…‘ (Snake interview).

Teacher development has social, personal and professional dimensions (Bell & Gilbert, 1996). In this particular student teacher’s case these dimensions seem particularly important: she found it difficult to accept her new role. The following quotation from Marris (1974, p. 156-157) may explain how this experience might have affected her, as the Snake interview illustrates: Occupational identity represents the

accumulated wisdom of how to handle the job derived from their own experience

and the experience of all who have had the job before and share it with them.

Change threatens to invalidate this experience robbing them of the skills they

have learned and confusing their purposes, upsetting the subtle

rationalisations and compensations by which they reconciled the different

aspects of the situation. (Marris, 1974,

p. 156-157) Further, her high-status image of being a teacher made her critical of the teachers in schools in which she worked as a student: Schoolteachers don’t dress well. It’s so

unprofessional. Would people go to an office with no tights on, in sort of

sandals, sloppy sandals and not tights...It’s important for society. They then

look up to teachers and they think ‘Oh, yeah they look very smart’…a formal

dress gives you the idea that this job is important…. it’s a job that deserves

respect … (Snake interview).

Although any interpretation is speculative, one can surmise that, since she had had 14 years of teaching experience before starting the MFL PGCE course, she had established her sense of professional self and her competence. Further, because of ST3’s image of herself and her status relative to the other student teachers, she seemed to be cautious in disclosing any developments in her beliefs, perhaps resisting any challenge to her previous learning and sense of competence, although she had volunteered to take part in the interviews. Finally, from a methodological point of view, the Snake technique proved valuable in helping her to articulate further her firmly held beliefs and their sources, something that she found difficult when answering the researcher’s questions in the more traditional interviews. ‘Turned upside down’: ST14 and ST16 These two student teachers seemed to experience greater changes in their beliefs compared to the rest of the group in the main study. Additionally, they seemed to be the most influenced emotionally by the challenge to their beliefs, by the experiences they had and by the information and knowledge presented to them: hence the title ‘turned upside down’. ST14 Background ST14 is a French applied languages graduate in her 30s. Previously, she had had no teaching experience of any kind, unlike the majority of student teachers. She said that she found teaching exciting and motivating and that she believed that she could take “a lot of nonsense” from her future pupils. Interview I Insights gained from her own learning experiences, often quite negative, appeared to influence the way she wanted to teach and her approach to pupils. As she had felt that she was “crap” at languages and that she was not “gifted”, she hoped she would make her future pupils understand that language learning was not “out of reach.” Despite “loving grammar” herself, she felt early introduction would put pupils off. Having experienced boring lessons herself, she was determined to make hers fun, with group work, role play, pictures and stories. For her a good language teacher had a good sense of humour, was “jolly”, “a bit mad”, “not too boring” and “not too conventional”, like a “mother”, able to empathise but also keep their distance when necessary. She preferred teaching pupils with the same ability level, rather than mixed, but would like to teach pupils with low ability because of her own learning experiences. Interview II After she had done a considerable amount of observation and had started microteaching, she seemed to be quite disillusioned and discouraged. Her beliefs about teaching and learning seemed quite “upside down.’ Unlike before, she thought that grammar should be taught straight away as pupils did not know anything about grammar. She no longer wished to make her lessons fun. On the contrary, she would make them work harder. She explained: “I realised if you make it too much fun, the pupils don’t take it very seriously and the lesson turns into a circus.” She now thought that she wanted to teach in a high ability classroom where pupils would be interested and want to learn using individual work that is easier to assess and control. Teachers should be “quite strict”, “down to earth”, though she thought that such teaching was “boring.” She added “I am very disappointed in myself, because I have changed completely. From a nice, easy going person and I have become quite strict, and stern and impatient. I think I’ve changed a lot really.” Also, she had started wondering if she should be a teacher. Interview III At the time of third interview ST14 seemed more relaxed and more confident. She agreed with most of the issues she mentioned in the second interview regarding role of grammar, making lessons less fun, mixed ability groups. Her conception of teachers was more sophisticated: a good language teacher was someone who had a good knowledge and understanding of second language acquisition, someone who could empathise with her pupils, but not be unconventional. Instead, she thought teachers should have ground rules so that pupils would know “where they are.” She said she realised that being “herself” was not possible when teaching. She also introduced some new issues about learning and teaching: pupil autonomy, pupil centred teaching, the importance of seating arrangements for classroom management and so on. She explained the impact of the block teaching practice experience: “[it] literally almost changed my beliefs in a way. My beliefs were much more liberal. Now I have become a bit more conservative.” Snake interview and comments The Snake interviews provided much of the information in relation to her background. Ever since she was put off by a teacher from the idea of becoming a veterinary surgeon, teaching had been at the back of her mind. She admired one of her French teachers who was “very good”, “quite witty”, and “quite intellectual.” She was impressed with the fact that a teacher “could have a big influence on someone”, “could make a big difference to someone’s life.” However, upon the advice of her parents, she first trained and worked for four years as a nurse. She was happy with her job but feared that one day she would regret it, would not be fulfilled, if she did not get a degree and teach. She needed “more intellectual prestige.” When she came to England, she enrolled in a college to do the General Certificate for Secondary Education (a qualification normally taken at age 15 or 16 in England in a variety of subjects) then an Access to Higher Education course. When she was offered a place at a university, she was “over the moon.” The choice of subject matter was not difficult, French and applied linguistics being the “easy options.” She said: “I always wanted to teach but I didn’t care what I would teach in a way.” After getting her degree, she applied to the teacher training course. It was “a fight to get a place.” When she was accepted, it was like a “lifelong dream becoming true.” On entry into the course, it was evident from the various data sources that she was heavily influenced by her own language learning experiences, the only source for her beliefs about language learning and teaching. In the Snake chart, she annotated her experience in the course as a “big disappointment.” She was disappointed because, although previously she thought that teachers were “influential and intellectual”, now what she saw in the staff room in the school where she practised teaching “annoyed” her. What she saw was “narrow minded people who complained all the time”. Further, the whole course experience had an effect on her beliefs in a complicated way: her experience of teachers and teaching had contradicted what she had expected based on her previous experience as a learner. Nevertheless, in the questionnaire the end of the year, she indicated that she felt confident about the prospect of starting teaching; however, she wrote: “I don’t know if I still want to do it as much as I did [at the beginning]”. ST16 Background ST16, also in her 30s, has a degree in English, was born in France into an ethnic minority group and is bilingual. She had taught English as a foreign language in France (4 years), and French as a foreign language in the U.S.A. (2 years). She was more attracted to the subject than the profession but she would like to “act as a role model” especially for pupils coming from ethnic minorities: her position, she hoped, would encourage them to study hard and realise that “they can do it.” To her, teaching French means teaching people “to be open minded”, “to accept differences” and “to be tolerant.” This “social dimension” of teaching is what she liked most about her job. It is a job that has challenges, that requires “patience”, “tolerance”, “working on yourself” and on “who you are” to develop yourself as a teacher. Interview I ST16 indicated that classroom size, such facilities as television, video and activity books were important elements of teaching but the primary element of teaching was the teacher’s personality. Good language teaching included being good at “entertaining” pupils, bringing about dynamism and energy in the classroom and when necessary, acting as a “clown”, though wearing “nice and tidy, charming clothes.” She said that teaching was about one’s “personality”; one’s teaching style reflects one’s personality and, because it is a demanding job, teachers should really like teaching. Very often, she referred to her own language learning and teaching experiences. Occasionally, she ascribed some of her beliefs to the experiences she had during her observations in schools. Interview II By this time, ST16 was quite disappointed: she realised that there was not one “excellent language teaching method” and “excellent personality” and that teaching children was very different from teaching adults. In schools, she was “forced” into being somebody she was not like, for example by being strict. Also, she found out that her idea of fun did not match her pupils’ and that they each had different learning styles. She still thought that teachers needed to be dynamic but she discarded the idea that teachers should be “clowns”, instead believing teachers should “calm down” pupils. ST16 had started questioning the concept of motivation as well. She said that earlier she “was very idealistic” and “very na´ve” because she had made the “mistake” of believing that pupils would be as motivated as she had been. Once again, she was misled by her own characteristics, her own language learning experiences: “because I didn’t know that it would be so different with children.” As a result of all these experiences, she wanted to use more “traditional ideas.” Being a professional had a new meaning for her now. Interview III During this interview, she introduced such new terms acquired from the course such as “pupil autonomy”, “pupil centred teaching”, “collaborative learning”, “differentiation”’ and “the ability to reflect on your work.” She still put a great emphasis on teachers’ personalities - being a good “entertainer”, having “self-control” and “patience.” In relation to her own personality, she claimed:

Snake interview and comments Much of the information about the background of this particular participant comes from the Snake interview. The Snake chart drawn by this participant provided a detailed account of how some of the constructs she held about language and teaching evolved over time. She seemed to recognise that they had been “particularly influenced consciously, or unconsciously, by formative experiences” (Pope & Denicolo, 1993, p. 540). She revealed the influence of her siblings who had all been very good at languages: she had worked hard at school and particularly liked foreign languages. Teaching was never an option in her mind until she went to the States to improve her English. Later in that year, she experienced teaching for the first time and she “loved” it and was very “successful”: she started considering teaching “as a serious option” The language teachers she met there had a great influence on her. When she returned to France, she started to work as a teacher. Compared to the other student teachers in the main study group, ST16 had had a relatively long teaching experience in different contexts. For this reason, one would expect that she would experience less disillusionment than those student teachers, like ST14, who had less teaching experience than her. However, it seemed that from her previous experiences with adult learners she made generalisations that were not applicable to the new teaching context with children (cf. Kelly’s Range Corollary in the Introduction - constructs have a limited range of applicability). Also, she was not familiar with the English education system and the responsibilities of teachers, so the PGCE course changed the way she looked at teaching and her role as a teacher: “it made a dramatic difference because you learn how schools work, function and it helped me to adapt ... to fit the English context.” Finally, it appeared that she was making more conscious adjustments than ST14. For instance, both student teachers stressed that the “authority” concept was alien to them, but ST16 had found a way to accept it while ST14 rejected it. DISCUSSION Overview This study focused on sources of PGCE students’ beliefs about teaching on entry to the course and how these beliefs developed through the year, particularly for three student teachers with extreme development patterns. A constructivist technique called Snake illuminated the individual belief development, or strengthening of belief in one case, of these particular student teachers, and provided data that suggests that Kagan’s ‘inflexibility’ thesis and Zeichner et al’s assertion that training programmes are not very powerful interventions are rather sweeping generalisations. The students who had abandoned the course in its early stages and the majority who did change their views to some extent attest to this while the in-depth work with ST14, ST16 and ST3, as extreme examples, provides some insight into reasons why or how students change their views during the course to different degrees. Observations about belief development The data from the first set of open-ended interviews showed that the two participants, ST14 and ST16, appeared to be holding rather optimistic, indeed idealistic, beliefs about the persona of a language teacher and what should be done to teach languages effectively. This supports other studies that found that the first teaching experience was not what novice teachers expected so that previous beliefs and optimism were destroyed when confronted by reality, being replaced by disillusionment (O’Connell, 1994; Rust, 1994, Weinstein, 1989, 1990). Other studies have shown that early teaching concerns represent potential stressors that may place novice teachers at risk of experiencing frustration, tension, anxiety, praxis, shock and alienation from their work (Byrne, 1999, 1994; Haritos, 2004; Lens & DeJesus, 1999; Veenman, 1984; Wideen et al., 1998; Woods, 1999). ST14 and ST 16 certainly provided evidence of all these reactions, though to different extents individually. In the literature on student teaching and belief development, other patterns arise in the way student teachers initially construe teaching: they usually emphasise the humanistic qualities of teachers (Mahlios & Maxon, 1995) while they tend to put an emphasis on the importance of positive personality traits (Sugrue, 1997; Virta, 2002). Similar patterns were observed in the initial conceptions of student teachers ST14 and ST16. Because of her 14 years of teaching experience, one could assume that ST3 would have established her sense of professional self and her competence, and the Snake data supported this – she did not seem to change. In relation to experienced practitioners, Rudduck maintains (1988, p. 208): “If we accept that practitioner’s own sense of self is deeply embedded in their teaching it should not be surprising to us that they find real change difficult to contemplate and accomplish.” ST3 not only demonstrated this effect in what she said but in her defensive attitude when contending that she was learning nothing new and when describing the discomfort she felt at being labelled a “learner teacher”. The snake interview data from ST14 and ST16, however, demonstrate that it is not simply experience per se of teaching that is the critical factor because ST16 had had experience (6 years) of teaching albeit in a different context. While ST14 was challenged by differences between her own past experience as a pupil and her current experience as a teacher, ST16 found a mismatch between two different kinds of teaching experience, as their responses demonstrated. Observations about the Snake Technique: This study illustrates how the life histories of the participants had an influence on the constructs they held about teaching and learning. It also demonstrates that a structured and facilitative intervention, in addition to traditional interviews, helps people to articulate the constructs they employ in particular situations. This echoes the following quotation: Contradictory as it may seem, the

anticipatory power of constructs lies in the past. In order to come to an

understanding of the present we need to compare and contrast it with

experiences we have had previously and use these to predict the future…Thus

biography has an important influence on the constructs we bring to bear on any

situation in which we find ourselves. The ones that predominate while engaged

in a particular activity are likely to be ones that have served us well in what

appear to have been similar circumstances in the past. Since much life is

hectic, encouraging action rather than reflection, we are often unaware of

constructs guiding that action and from whence, in our pasts, these are

derived. This means that, although well-established, some of our personal

constructs may now be redundant or even counter-productive. However, unless we

become consciously aware of them, they cannot be challenged, and they remain

influential in orientating our being. (Denicolo, 2003, p. 129)

In particular the Snake technique proved useful when searching for answers to the questions that arose at one critical stage of the study. The value of the technique in this study can be summed up as follows. The Snake interviews:

CONCLUSION The focus on the use of Snake interviews within a complex study has allowed us to illustrate its general advantages as a research instrument, particularly that of adding data that otherwise would be difficult to access. (Data from the full study can be found in Cabaroglu, 1999; Cabaroglu & Roberts, 2000.) However, writing from this specific perspective has also highlighted for us an additional benefit in that it provided a storyline into which we, along with the interviewees, could plug the data gleaned from other sources, further illustrating the power of constructivist tools. Without it the other data would be akin to snippets of film viewed from only part-way through. The Snake interviews provided us with the essence of the plot in relation to teaching and learning from the interviewee’s perspective and gave more substance to their disclosed characters. In turn, it allowed them to stand back and view how their own story was unfolding, how their present linked with their past, helping each to make more sense of the confusion that pervades a student teacher’s life. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| REFERENCES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Albanese, M. (1997). Double-edge blade of

PCP: a powerful tool for reflection and verification. Paper presented at

BERA Research Students Conference, University of York, York, England. Bell, B. & Gilbert, J. (1996). Teacher development: A model from science education. London: The Falmer. Byrne, B. M. (1994). Burnout: testing for the validity, replication, and invariance of casual structure across elementary, intermediate, and secondary teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 31, 645-673. Byrne, B. M. (1999). The nomological network of teacher burnout: A literature review and empirically validated model. In R. Vandenberghe & A. Huberman (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout (pp. 15-38). New York: CUP. Cabaroglu, N. (1999). Development of student teachers’ beliefs about learning and teaching in the context of a one-year Postgraduate Certificate of Education Programme in Modern Foreign Languages. PhD thesis, University of Reading, Reading, UK. Cabaroglu, N. & Roberts, J. (2000). Development in student teachers’ pre-existing beliefs during a 1-year PGCE programme. System, 28, 387-402. Clark, C. M. (1986). Ten years of conceptual development in research on teacher thinking. In M. Ben-Peretz, M. Bromme & R. Halkes (Eds.), Advances of research on teacher thinking. (pp. 7-20). Lisse: Swets and Zeitlinger. Clark, C. M. & Peterson, P.L. (1986). Teachers’ thought processes. In M.C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on thinking (3rd ed.). (pp. 255-296). New York: Macmillan. Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research design: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. Denicolo P. M. (2003) Elicitation methods to fit different purposes. In F. Fransella (Ed.), International handbook of personal construct psychology (pp.123 -131). Chichester: John Wiley. Denicolo, P. & Pope, M. (1990). Adults learning-teachers thinking. In C. Day, M. Pope & P. Denicolo. (Eds.). Insights into teachers’ thinking and practice. (pp. 155-169). London: Falmer. Haritos, C. (2004). Understanding teaching through the minds of teacher candidates: a curious blend of realism and idealism, Teaching and Teacher Education, 20, 637-654. Iantaffi, A. (2004). A researcher’s experience of constructivist techniques. Unpublished presentation, BERA/TLRP Master Class, University of Reading, Reading, UK. Kagan, D. (1992). Professional growth among preservice and beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 62, 129-169. Kelly, G. A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs: A theory of personality. (Vol. 1&2). New York: W. W. Norton. Lens, W. & DeJesus, S. N. (1999). A psychosocial interpretation of teacher stress and burnout. In R. Vanderberghe & A. Huberman (Eds.), Understanding and preventing teacher burnout. (pp. 192-202). New York: CUP. Mahlios, M. & Maxson, M. (1995). Capturing preservice teachers’ beliefs about schooling, life, and childhood. Journal of Teacher Education, 46, 192-199. Marris, P. (1974). Loss and Change. New York: Anchor. Mason, J. (1996). Qualitative Researching. London: Sage. Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. Munby, H. (1982). The place of teachers’ beliefs in research on teacher thinking and decision making and an alternative methodology. Instructional Science, 11, 201-225. O’Connell, R. I. (1994). The first year of teaching. It’s not what they expected. Teaching and Teacher Education, 10, 205-217. Oppenheim, A. N. (1992). Questionnaire design, interviewing and attitude measurement. London: Pinter. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. New Bury Park, California: Sage. Pope, M. L. & Denicolo, P. (1993). Intuitive theories – a researcher’s dilemma: some practical methodological implications. British Educational Research Journal, 12, 153-166. Pope, M. L. & Denicolo, P. (2001). Transformative education: Personal construct approaches to practice and research. London: Whurr. Rust, F. (1994). The first year of teaching: It's not what they expected, Teaching and Teacher Education, 10, 205–217. Sugrue, C. (1997). Student teachers’ lay theories and teaching identities: their implications for professional development. European Journal of Teacher Education, 20, 211-225. University of Reading. (1997/1998). PGCE secondary modern languages, method handbook, Reading, England. Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 54, 143-178. Virta, A. (2002). Becoming a history teacher: observations on the beliefs and growth of student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 687-698. Weinstein, C. S. (1989). Teacher education students’ preconceptions of teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 40, 53-60. Weinstein, C. S. (1990). Prospective elementary teachers’ beliefs about teaching: implications for teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 6, 279-290. Wideen, M., Mayer-Smith, J. & Moon, B. (1998). A critical analysis of research on learning to teach: making the case for an ecological perspective on inquiry. Review of Educational Research, 68, 130-178. Woods, P. (1999). Intensification and stress in teaching. In R. Vanderberghe & A. Huberman. (Eds.). Understanding and preventing teacher burnout (pp.115-139). New York: CUP. Zeichner, K. M., Tabachnik, B. R. & Densmore, K. (1987). Individual, institutional, and cultural influences on the development of teachers’ craft knowledge. In J. Calderhead (Ed.), Exploring teachers’ thinking. (pp. 21-59).London: Cassel. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ABOUT THE

AUTHORS Dr. Nese Cabaroglu is a lecturer in the English

Language Teaching Division of Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey. Dr. Nese Cabaroglu is a lecturer in the English

Language Teaching Division of Cukurova University, Adana, Turkey. Email: ncabar@cu.edu.tr  Professor Pam Denicolo is a psychologist

and an Honorary Member of the RPSGB. In addition to leading the Centre for

Inter-Professional and Postgraduate Education and Training and being the

Director of Postgraduate Research for the School of Pharmacy, she is also the

Director of the Graduate School for

the Social Sciences, serving on the University Committees and Boards and on

national committees concerned with Postgraduate Research issues. Her research

approach is based in Personal Construct Psychology (PCP) and she leads the Research Centre for PCP

at the University of Reading, England. Professor Pam Denicolo is a psychologist

and an Honorary Member of the RPSGB. In addition to leading the Centre for

Inter-Professional and Postgraduate Education and Training and being the

Director of Postgraduate Research for the School of Pharmacy, she is also the

Director of the Graduate School for

the Social Sciences, serving on the University Committees and Boards and on

national committees concerned with Postgraduate Research issues. Her research

approach is based in Personal Construct Psychology (PCP) and she leads the Research Centre for PCP

at the University of Reading, England. Email: p.m.denicolo@rdg.ac.uk |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| REFERENCE Cabaroglu, N., Denicolo, P. M. (2008). Exploring student teacher belief development: An alternative constructivist technique, snake interviews, exemplified and evaluated. Personal Construct Theory & Practice, 5, 28-40, 2008. (Retrieved from http://www.pcp-net.org/journal/pctp08/cabaroglu08.html) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Received: 29 March 2007 – Accepted: 1 September 2008 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

ISSN 1613-5091

| Last update 15 September 2008 |